Blog - The best travel insights and top travel tips

Welcome to the Mountain Kingdoms blog. We have been walking and trekking the world for over 36 years and here we share our holiday recommendations, travel pointers and favourite mountain views.

First time trekkers in Nepal

This spring, our new Operations & Marketing Assistant, Jess, decided to tackle the Annapurna Sanctuary Trek. Despite being only 23, Jess is already a veteran traveller having been to India, Japan, New Zealand and Southeast Asia, to name but a few of the far-flung destinations she’s visited. However, she’d never been to Nepal and was keen to experience it for the first time.... Read more

The Best Places to Visit in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka may be small in size, but this teardrop-shaped island is one of Asia’s most captivating travel destinations. Nestled in the Indian Ocean, this tropical paradise boasts a stunning mix of diverse landscapes, rich cultural heritage, and breathtaking beaches that appeal to every traveller. ... Read more

The Best things to do in Bhutan

Whether you’re planning on spending a week or a month in Bhutan you’ll not be short of things to do. It may be small, but the Thunder Dragon Kingdom, is packed with no end of possibilities whether you want to tour the cultural sights, explore the towns, discover the countryside or head to the Himalaya on an adventurous trek. ... Read more

The Best Everest Hiking Boots: What You Need to Know About

Maybe you thought that taking the plunge and finally committing to trekking to Everest Base Camp (EBC) was the hard part. Wrong, that’s just the beginning! Tackling one of the world’s most famous treks requires not only physical preparation but also the right gear - especially the right Everest hiking boots.... Read more

What is the Best Time of Year to Trek to Everest Base Camp?

Everest Base Camp (EBC) is one of the world’s most iconic locations, and the trek to reach it is a bucket-list adventure for many. As one of the most sought-after and well-known treks in the world, it offers breathtaking views of the Himalaya and a chance to experience the unique culture of Nepal and the Khumbu (the Sherpa name for the Everest region). However, timing is crucial for an enjoyable and successful trek.... Read more

Planning a trip to Bhutan: Everything you need to know

Visiting the tiny Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan has long been considered beyond the reach of the ‘average’ traveller, but those who venture into the Land of the Thunder Dragon are rewarded with an enthralling culture and spellbinding scenery. This remarkable country stands out for its unique approach to tourism, prioritising environmental sustainability and the happiness of its people over mass tourism.... Read more

Mount Kilimanjaro vs Everest Base Camp: The Key Differences

When it comes to bucket-list treks, Mount Kilimanjaro and Everest Base Camp are two of the most iconic adventures in the world. Whether you're climbing Africa’s highest peak or trekking through the heart of the Himalayas, both offer an unforgettable experience and are very popular among adventurers. ... Read more

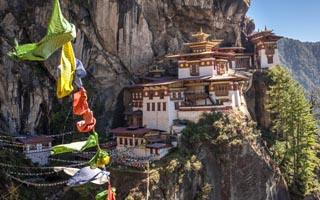

A Guide to Festivals in Bhutan

Festivals are a significant part of Bhutan's culture and are central to the living Buddhist faith in the kingdom. Most festivals, also known as 'tsechus', are of great religious significance and are mostly celebrated through music and ritual masked dances called 'chams'. Tsechus attract large numbers of Bhutanese people, dressed in their finery, as they believe by attending these special celebrations they gain religious merit as well as enjoying a fine social event. ... Read more

The Best Places to Visit in Bhutan

Bhutan, known fondly as the ‘Land of the Thunder Dragon’, is a travel destination unlike any other. Untouched by mass tourism, this Himalayan kingdom draws visitors in with its blend of rich culture, stunning landscapes, and deep spiritual traditions. But what makes this country truly beautiful isn’t just the spectacular scenery, it’s its commitment to the Gross National Happiness scale which prioritises the well-being of its people and environment over economic growth.... Read more

The Five Best Things to do in Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan is a country brimming with rich history, vibrant cultural heritage, and stunning landscapes that range from majestic mountains to serene deserts. Known as the heart of the ancient Silk Road, Uzbekistan offers a unique blend of the past and present, making it a fascinating destination for travellers. ... Read more